Mohs Surgery

Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery is the most precise way to remove skin cancers that are in either difficult locations or have poorly defined borders. Dr. Frederic Mohs invented the procedure over 70 years ago. He discovered that if he removed a skin cancer and drew a precise map, that the skin cancer could be tracked out more easily. This process was originally carried out with a fixative paste. In the 1970’s the process was refined with the use of frozen sections. This modification dramatically speeds up the whole procedure.

Currently the state of the art for Mohs surgery involves the dermatologic surgeon acting not only as the surgeon but also as the pathologist and usually the reconstructive surgeon.

Mohs surgery is designed to have the highest cure rate, approaching 100%, for the treatment of routine skin cancers such as basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. It is also designed to conserve as much normal tissue as possible. The more normal tissue that is spared, the less scarring results after the surgical procedure is completed.

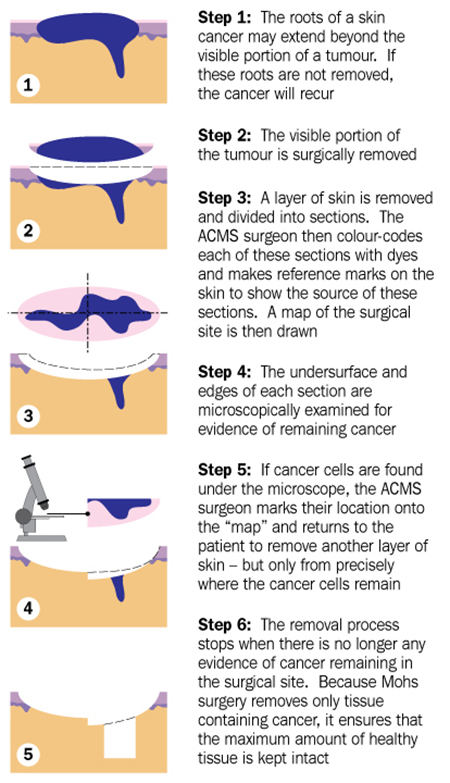

The procedure itself involves numbing of the skin around the tumor. A small margin is excised around the obvious tumor. The tissue that is removed is often divided into one to four specimens. The specimens are color-coded and then processed. Processing involves freezing the tissue and cutting thin specimens that are placed on microscope slides. These slides are then stained in a routine fashion and examined microscopically. The Mohs surgeon is able to precisely determine if skin cancer is present and where it is present.

If the microscope slides are found to be negative for skin cancer, then no further surgery is necessary. However, if they are positive for skin cancer then the Mohs surgeon can go back precisely to the area where there is residual skin cancer and remove a little more. This process is repeated until there is no residual skin cancer left.

Often the Mohs surgical defects are repaired following the Mohs surgical procedure. These skin defects are either repaired with a local flap (skin is moved into the defect from adjacent normal skin) or a skin graft is applied. Postoperative pain is usually minimal. Tylenol is typically the only analgesic that is needed. Although patients get scars, the ultimate scar is usually difficult to see and cosmetically quite acceptable.